Adhering to regulations is crucial for any business, and telephony providers are no different. PBX installations in particular, on top of adhering to customer expectations, must also follow legal standards in order to steer clear of fines, litigation and other significant penalties.

In the US, some of the most important telephony regulations are those around Enhanced 911, or E911. These are crucial to know about because they don’t simply regulate how you sell PBXs or how they may be used — instead, they specify exactly how dialing emergency numbers must work for a multi-line telephone system (MLTS).

If you plan at any point on selling an MLTS in the United States, these are the main points of E911 regulations you need to know.

What Are E911 regulations?

Like the name implies, E911 regulations require that any time 911 is dialed, the call itself communicates additional information to emergency dispatchers.

In short, E911 laws require that every 911 call must also convey:

-

- A callback number for emergency services (either for the device placing the call or a central agent on the site of the MLTS)

- The location of the device that called 911

These requirements were put in place by two federal US laws: Kari’s Law and Ray Baum’s Act.

Let’s dive into both of them now for more detail on the technical requirements behind E911.

The E911 Laws

1. Kari’s Law

Adopted by the Federal Communications Committee in 2019, Kari’s Law establishes two main requirements for 911 calls.

The first requires that emergency services are immediately contacted when “911” is dialed on an MLTS device, without having to dial for an external call. In other words, the dialer must not have to take an additional step before sending the emergency alert: simply entering “911” on the device must be enough to contact emergency dispatchers.

The second part of this law is more complex. This section specifies that any time a 911 call is dialed through an MLTS, a notification is simultaneously sent to a “central operator” who is on the same premises as the MLTS.

This “operator” can be most anything: a front desk, a security office, the IT department or similar. The agent just has to be a person who’s on premises and will actually see the alert.

Likewise, there’s room for you to decide what the notification is. To meet legal requirements, the alert can be an email, a text message, a screen alert or any other electronic message. It simply has to be sent right as the PBX issues a 911 call, and it must be prominent enough that the operator on the premises is unlikely to miss it.

So, what exactly should this notification say? Here, requirements become stricter.

Per Kari’s Law, this notification must convey, at a minimum, the following information:

-

- The fact that a 911 call has been made

- A valid callback number for emergency services

- Details on the caller’s location, which the MLTS also sends to the public safety answering point (PSAP) as part of the 911 call

It’s worth noting that points 2 and 3 can, in some instances, be waived. According to the law, if it is “technically infeasible” to add this information to the notification, it isn’t required to provide it.

However, if you can’t provide that info, you will have to prove that it’s “infeasible” for the system to provide it, which of course will be a complicated process. All in all, it’s best to simply include that information from the start to make things move most smoothly.

2. Ray Baum’s Act

While not entirely about 911 calls, Ray Baum’s Act features a portion that applies to E911 considerations.

According to Section 506 of this act, all 911 calls must include a “dispatchable location” embedded in the call (regardless of what device they originate from).

“Dispatchable location” here means a specific street address, plus any additional information required to pinpoint the exact calling location, like apartment number or suite number. In short, the call must also carry data specifying exactly where emergency dispatchers should go.

This ties into point 3 from the second part of Kari’s Law mentioned above, and the good news is by covering this requirement from Ray Baum’s Act, your phone system will fulfill that part of Kari’s Law as well. It’s simply worth mentioning because by not having it, you run the risk of violating two regulations.

It’s also important to note that all devices, both fixed and unfixed, must be in compliance with Ray Baum’s Act by January 6th, 2022. So if by early 2022, your unfixed devices can’t report a dispatchable location to 911 operators, you will be considered in violation of this law.

So in brief …

Here’s a quick overview of what your phone system needs to meet E911 regulations:

- If you’ve installed an MLTS, each phone on the PBX must reach emergency services immediately just by dialing “911” (not requiring the dialer first push a key to make an outbound call).

- Any time 911 is dialed, the MLTS must also send a prominent notification to a central operator on site, and the notification must include:

- The fact that a 911 call has been made

- A callback number that emergency services can reach

- Information on the 911 caller’s location

- Any system must also tell emergency services the street address (and, if necessary, apartment or room number) from which the call was made.

What happens if you’re not compliant?

If you install an MLTS without meeting the three requirements above (or a phone system that doesn’t fulfill point number 3), your business will become liable under federal law. (It should go without saying this isn’t a preferred state to be in.)

Specifically, businesses that don’t adhere to these laws face fines of up to $10,000, with a further fine of $500 each additional day that you are not in compliance.

For US telephony providers, staying in business all but requires fulfilling these federal regulations.

How do you ensure compliance?

Obviously, there are two ways to stay in compliance with these laws: either have a system that’s compliant from the beginning or alter a noncompliant PBX to become compliant.

If you’re taking that latter option, the good news is that creating compliance with Kari’s Law is fairly straightforward. As any technician can tell you, removing external dialing requirements from 911 calls is not a hard exception to add to a dialplan. Likewise, it’s not much of a hassle to make an MLTS send the required notification any time 911 is dialed from it.

However, the bad news is that guaranteeing compliance with Ray Baum’s Act is nearly impossible without support from your vendor.

If your devices don’t already have capabilities for location reporting (or else don’t communicate this), adding in locations threatens to become a taxing process. Obviously, it will mean you’ll need to input the information yourself — but depending on your PBX’s setup and your vendor’s degree of involvement, this may turn into hours of manually adding the locations for each device into your system.

Consider also that this process is only for fixed devices. For unfixed devices, manually inputting locations will be outright unachievable — since, of course, users might move the devices from where you said they were.

Ideally, if your devices can’t provide location details upfront, your vendor will give you some easier way of adding in this info or even help with the process. If not, you’ll be stuck singlehandedly putting additional work into a system you no doubt already went through a lot of hassle to simply sell.

The easier alternative, of course, is to just use a system that’s compliant with these regulations to begin with and is supported by its vendor when it comes to inputting additional information.

What’s a good compliant system?

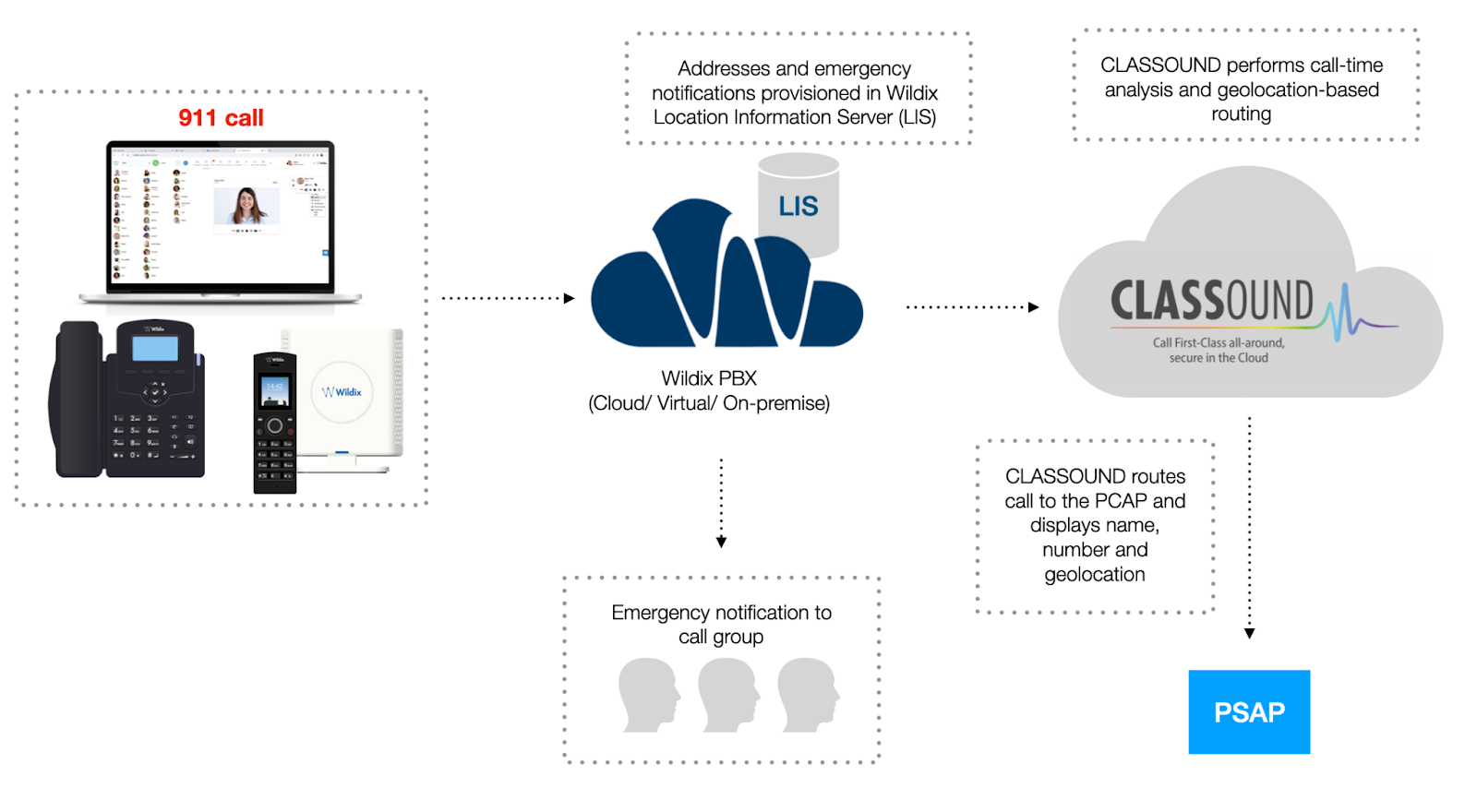

For a PBX that’s capable of acting as an MLTS and more — all while being fully in line with Kari’s Law, Ray Baum’s Act and other E911 regulations — an excellent choice is Wildix.

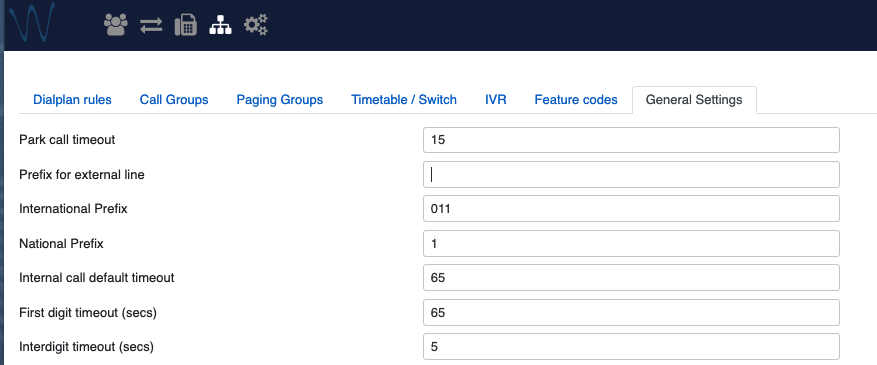

For starters, every Wildix system is ready-made to easily comply with Kari’s Law. By default, Wildix PBXs do not require a prefix to dial an external line.